Show! Don’t Tell!

When you don’t see where you are, all you can do is talk about it.

You get a suggestion for a scene:

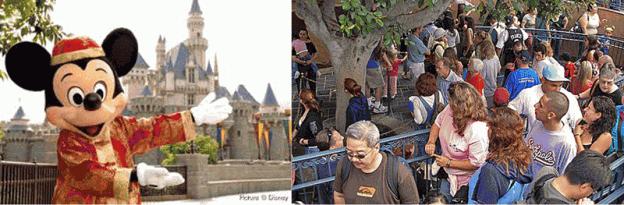

Who – A husband and wife.

Where – at Disneyland.

What – waiting to get on a ride.

Most players will begin the scene with dialogue something like this.

Husband: Well, well, dear isn’t this nice. Look! There’s the Matterhorn. Hi Mickey!

Wife: Sweetie, Let’s go on the Pirates of the Caribbean ride after this.

Husband: Do we have to? I’m tired honey, can we sit down?

What’s wrong with that, you ask? Nothing really. Except they told in dialogue what they should have been seeing (and didn’t) and they also told their relationship by calling each other honey and dear. After all, that’s what indicates to the audience that there is a husband and wife relationship, right? Where do you go from here? It is likely you’ll use Yes, And… and add more information. Maybe there’s an earthquake or Mickey starts hitting on the wife – and you’d have a pretty funny scene.

But what if you showed where you were and showed you were married rather than telling the audience what they just told you?

Where in Disneyland are you? How married are you and how do you feel about your wife?

Maybe you are standing in line, frustrated as you take a step forward every 30 seconds or so. You are standing in one of those long lines to get to a popular ride. You look over at your wife of many years and roll your eyes in disgust. She can look back at you with a shrug and a sheepish smile and try to keep you from getting mad. Maybe she takes out a camera and snaps a picture of you glowering. You duck under the bars that define the maze that keeps people moving and try to get to the exit.

Now you’ve showed that you are someplace specific and with someone specific by action and use of the where. Dialogue can come from that and the scene can grow from there. It becomes a more interesting thing than referring to information and having the audience do the work of imagining where you are and your partner doesn’t have to deal with cliché’s that say generic marriage. “Hi Honey, Yes dear.” Etc.

Many novice players ‘tell’(many veteran improvisers do too) It’s easy and a hard habit to break. I was very hung up on this early in my own training. I didn’t realize it at the time. I was very involved in making sure the audience knew what I believed they needed to know. I not only didn’t trust that the game’s focus would be strong enough to allow me to communicate, I did not have any experience of being in the space and really seeing where I was. It took me a while to see the where and to trust the focus. I was a very ‘heady’ player.

“Did they see and use the where?” Viola would ask.

“No.” the class would pronounce.

“I see.” I would say. “The Where is the key to our being involved with something other than the ‘story’”.

Viola often got frustrated with my wanting to ‘understand’ what she was after and my need to describe it verbally after the evaluation.

“It doesn’t matter! You didn’t let the where support you. That’s all!”

I still had to say it out loud to myself. Viola tolerated my need to make sense of my ‘lack of understanding’.

In retrospect, Viola was very patient in allowing me to flounder for so long. Which goes back to the first note in her tips and pointers – Don’t rush the student actors.

On the subject of floundering, I have had the urge many times, to ‘help’ a student player by showing him or her how I would do it. I have that need to ‘rescue’ students from the pain and frustration of not understanding the focus or the reason for a certain game. God knows I remember what it feels like to be in the dark and ask for illumination only to have the question deflected or ignored.

I have to remind myself that discovering the solution to a problem on your own makes it something that then belongs to you and the understanding that comes from the burst of insight becomes integrated into your own life and art in a way that is much more useful in the long-run. It also makes room for constantly finding new ways to solve problems.

Viola, I’m sure saw my frustration, but whenever I asked ‘how should I do this?’ she would bellow, “How do I know?! I’m not the answer book!”

I am purposefully avoiding the words “failing to get it”. Every attempt was a part of my education and the more I viewed it as failure the longer it took and the more distasteful trying again became.

Viola never told me I my work was ‘good’ or ‘bad’. She simply asked if I solved the problem. When the answer was “No.” she went onto another game.

I do remember once after a particularly trying workshop, I was driving Viola home. She wanted to stop at a grocery store and have me pick up something to make for dinner. We were parked in the parking lot of the supermarket and before I got out, Viola turned to me and said as nicely as she could.

“Gary, maybe you should try something else.” referring to the workshop. I had been in her class now for over a year and I did leave many sessions frustrated and bewildered. If Viola was aware of that she didn’t let on. But there it was. Here she was telling me I was not getting it.

It stung.

After a silence, I turned to her and said. “Viola, I may not be any good at this, but there is nothing else in the world I’d rather be doing.”

“Well, I respect that.” She said. “See if they have any lamb shanks.”

Postscript: Years later, I had the great good fortune to be teaching this work with Viola’s blessing and once, in her kitchen, as we were talking about a workshop I lead, she announced. “You know, I remember once I told you that you should try something else. Well, I was wrong. You are a fine player and coach.”

“Can I quote you Viola?” I asked.

She laughed. “Yes, go ahead.”

I would not have become the person and teacher I am without Viola’s patience and wisdom to let me find the light by myself with her as my often inscrutable sidecoach.